Vitali Vitaliev dusts off some pages from the 1900 Universal Exhibition in Paris.

One of the undisputed gems of my ever-growing collection of antiquarian guide-books is the compact brick-red volume of 1900 L’Exposition et Paris au Vingtieme Siecle – Guide to the 1900 Universal Exhibition and to Paris in the 20th Century, published by the famous women’s clothes retailer Bon Marche.

Apart from describing the main areas and sights of the French capital, the book – as the publishers announce proudly on its cover - contains “175 engravings and 9 coloured (sic) maps”.

An unexpected surprise is hiding behind the back flap, right underneath the foldable map of 1900 Paris: a somewhat battered, yet still perfectly usable, tape measure! The choosy turn-of-the-century Paris shoppers were thrilled to find it, I am sure.

Leafing through the slightly faded pages of that book, looking at the maps and touching the tape measure never fail to take me on a journey back in time to the year 1900, when Europe and the USA were still recovering from prolonged economic depression and the arts, technology and architecture were on the rise. It was a time of ground-breaking inventions and artistic masterpieces, many of which came to be represented at the 1900 Universal Exhibition.

It was also a time of hope, destined to be shattered 14 years later by the outbreak of the First World War.

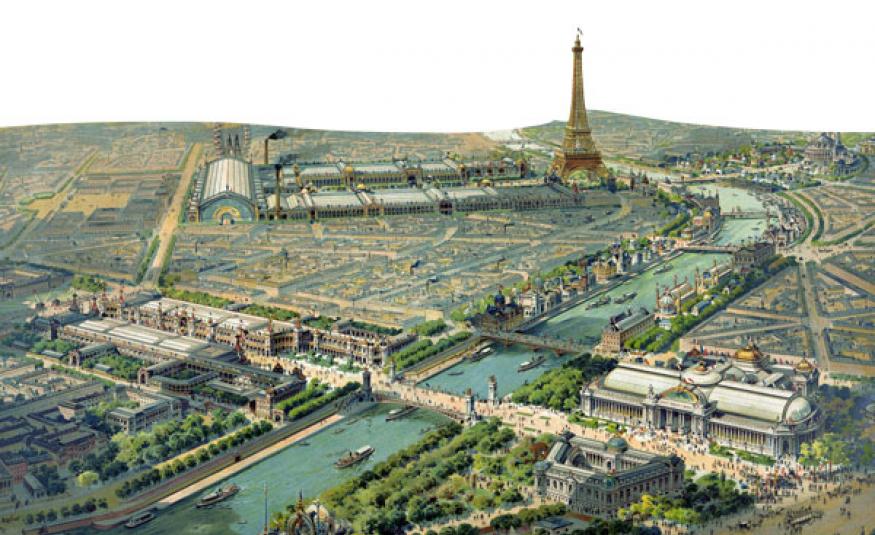

In the year 1900 the world was full of optimism, and that was strongly felt on all the 216 hectares and in all the 33 official pavilions of the Universal Exhibition, opened on 14 April 1900 by Emile Loubet, the President of France.

Donning our imaginary 1900 exhibition visitor attire (gentlemen – bowler hats and Norfolk jackets; ladies – puffed blouses and fluted skirts), let us take a quick tour of the show’s main highlights.

The Eiffel Tower, first displayed during the previous Paris Exhibition of 1889 (to mark the centennial of the French Revolution) stole the show again in 1900: prominent on the vast exhibition grounds, it was – for the first time ever – painted bright golden yellow, a mesmerising sight, according to witnesses. Just like the spectacular Alexander III Bridge, connecting Les Invalides with the Champs-Elysees, specially built for the 1900 Exhibition.

Lucky visitors (and there were over 50m of them for the duration of the Exhibition – from 14 April to 12 November, 1900) could not help being captivated by a huge Ferris wheel by the Palace of Electricity and fitted with five thousand multi-coloured incandescent lamps. There they could see, among other exhibits, the steam-powered generators which supplied electricity for all the pavilions; and Thomas Edison’s “moving boardwalk”.

It was there that inventor Rudolf Diesel first demonstrated his seemingly unassuming eponymous machine (then running on peanut oil) that was to change the world: by 1939, a quarter of global sea trade was fuelled by diesel power. Diesel himself was not destined to see his machine’s triumph, having mysteriously vanished from a cross-Channel ship as he was heading to a meeting in London in 1913.

But I digress.

Back in 1900, long queues gathered at the entrance to the Palace of Optics, with the Great Paris Telescope – then the world’s largest – inside. It could enlarge the image of the moon 10,000 times, and the visitors to the pavilion (two thousand at a time) could see it on a 144sqm screen.

Altogether, 21 of the 33 official pavilions were set aside for science and technology.

On top of the ‘official’ pavilions, the Universal Exhibition hosted 40 national ones. Those were temporary and, unlike the former, mostly designed in the Belle Epoch and Art Nouveaux styles, reflected the architecture of the exhibiting country.

The Russian pavilion, for example was modelled on the outlines of the Moscow Kremlin, the USA’s on the Capitol Building, and the British (designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens) resembled a Jacobean mansion. Buddhist-temple-like Chinese and Japanese pavilions were, reportedly, so beautiful that they were both purchased afterwards by the King of Belgium and transferred to Brussels.

A separate stretch of the Universal Exhibition’s territory was reserved for the so-called Colonial Pavilions, representing French, Dutch and Russian colonies and dependencies in Africa and Asia.

Neither a country nor even a dependency, the up-and-coming sculptor August Rodin had his own pavilion, in which his famous composition The Gates of Hell was first displayed, alongside his other sculptures.

One exhibit – part of the Agriculture Pavilion – capable of vying in popularity with the Palace of Optics was, for reasons that do not need explaining, the Champagne Palace, where free samples of French champagne were on offer.

Like all great history-making exhibitions, the 1900 ‘Exposition’ was accompanied by some truly momentous events: the showing of the first-ever motion pictures; the opening of the Paris Metro, with its distinctive Art Nouveau entryways; and the 1900 Paris Olympic Games – the first ever held outside Greece.

Among the less momentous events was the first (and so far the last) gathering, at which the mayors of all French cities, villages and towns – 20,777 in total – sat down together for an unhurried meal in the tents erected in the Tuileries Gardens. The other noteworthy (for some) occasion was the awarding of a gold medal for excellence to one of the American exhibits - Campbell’s Soup. This medal still features on some of the company’s soup labels.

It is always with regret that I close the 1900 Paris Exhibition Guide Book. Despite all the gruesome events that followed, most of the inventions and ideals it introduced have survived intact.

Wars, revolutions and natural disasters aside, the fact remains: the modern world wouldn’t have been quite the same without it.